The first millet varieties are thought to have originated in Africa and Asia; however, the oldest records of cultivation date back over 10,000 years in China. Mainly used for nourishment, millet's mild flavor agrees with a wide variety of culinary uses, and modern science is currently revealing its health benefits.

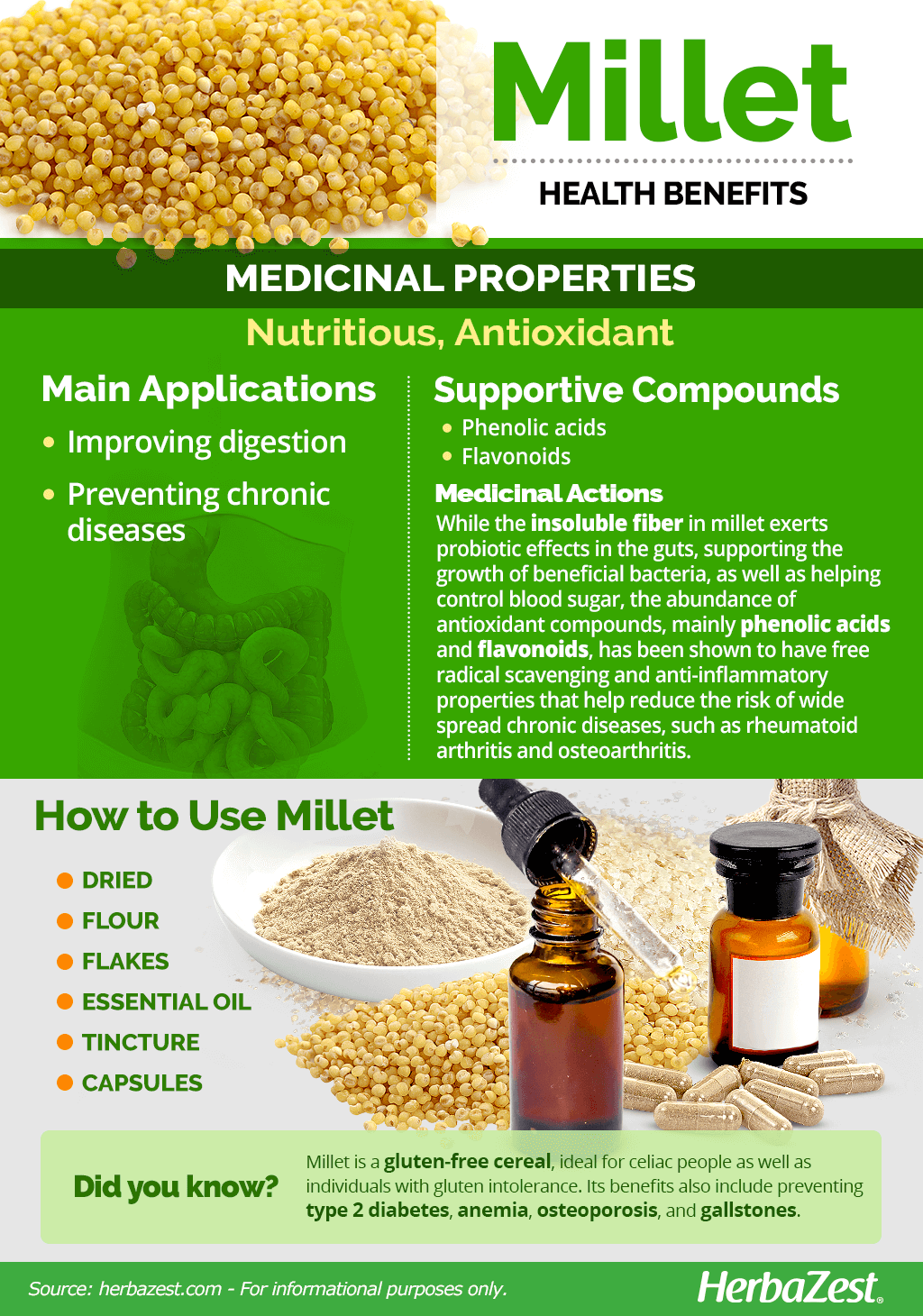

Millet Medicinal Properties

Health Benefits of Millet

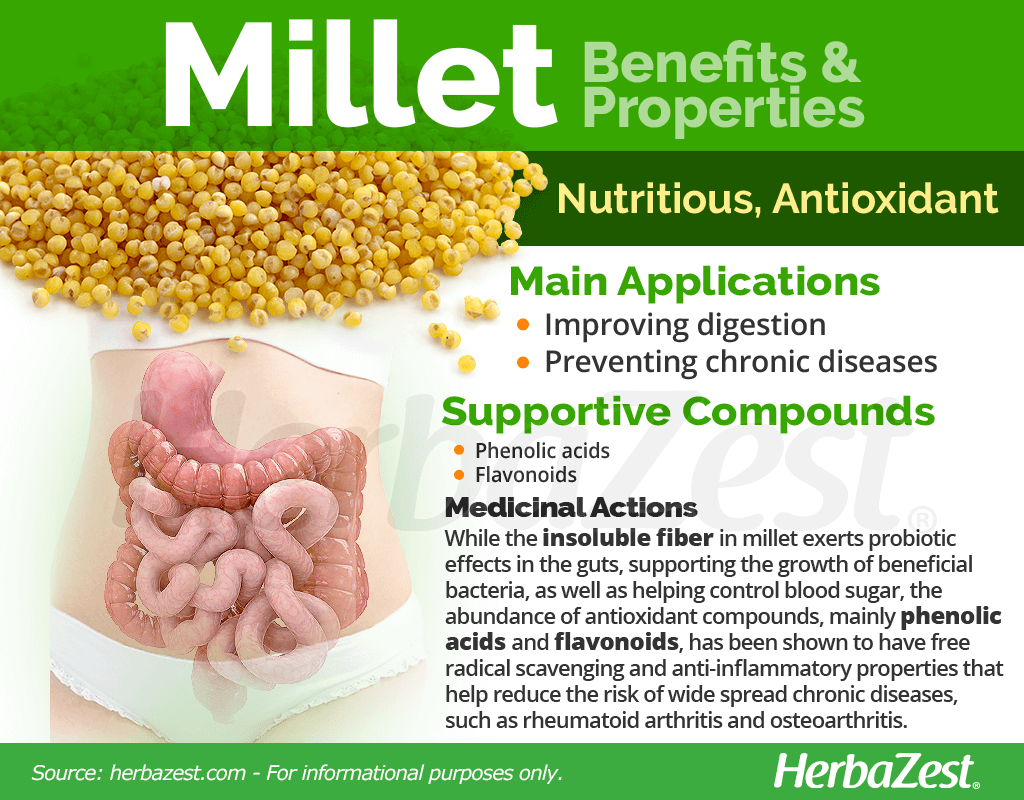

Millet has been predominantly used as food staple for thousands of years; however, its uses in folk medicine have been widely documented. This tall grass has been prescribed to treat a wide variety of health conditions, and modern science has been able to corroborate some of these traditional uses. The benefits of millet are numerous, but nowadays it is particularly useful for:

Promoting digestive health. Rich in dietary fiber, millet has prebiotic effects, which means it serves as food for the "good bacteria" in the gut. Millet's insoluble fiber, on the other hand, promotes smooth digestion and regular bowel movements.

Preventing chronic diseases. Millet in rich in antioxidants, which protect the body against free-radical damage and oxidative stress, thus helping prevent many chronic diseases.

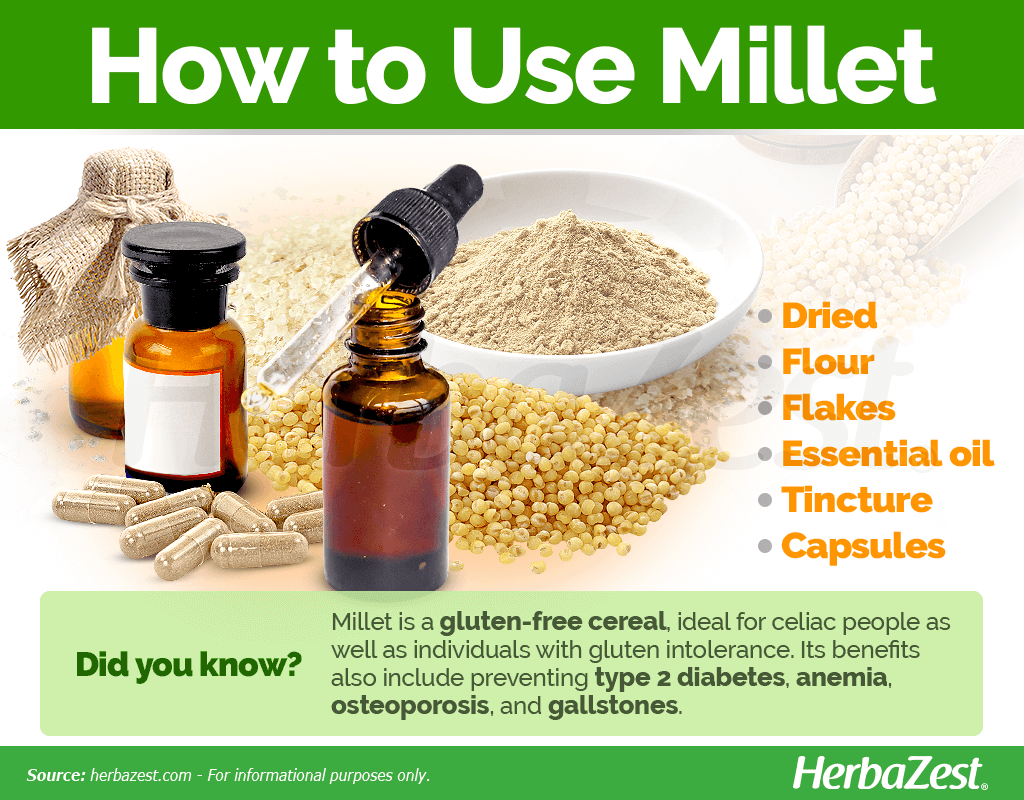

Additionally, the benefits of millet include preventing type 2 diabetes, anemia, osteoporosis, and gallstones.

IN KENYA, MILLET IS USED FOR TREATING INFLAMMATORY DISEASES, SUCH AS OSTEOARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS.

How It Works

Millet is particularly rich in phenols, which are the most powerful plant-based compounds in nature. The abundance of phenolic acids and flavonoids in millet has been shown to help reduce the risk of widespread chronic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.

The most important phenolic compounds in millet varieties are ferulic acid and chlorogenic acid, both of which have been linked to a reduced risk of chronic diseases, such as high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and liver injury.1

Millet's antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects are due to the influence of its flavonoids and phenolic compounds, which inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8), promoting the expression of the beneficial, anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10).2

Additionally, millet's insoluble fiber helps promote smooth digestion and regular bowel movements.

Other herbs that promote digestive health are flax, pear, and yacon, whereas anti-inflammatory properties can also be found in berries with high levels of antioxidants, such as acai, blackcurrant, and goldenberry.

Millet Side Effects

Millet is considered generally safe for human consumption, in both culinary and medicinal forms; however, ingesting great amounts of this cereal can excessively delay digestion, causing constipation.

Millet Cautions

In people with thyroid disease, daily millet consumption can further compromise the endocrine function and lead to metabolic disorders. Additionally, millet contains oxalates that can cause kidney stones as well as phytic acid that can hinder the absorption of nutrients in the gut.

- Medicinal action Antioxidant, Nutritious

- Key constituents Phenols, flavonoids

- Ways to use Capsules, Tincture, Powder, Essential oil, Dried

- Medicinal rating (3) Reasonably useful plant

- Safety ranking Safe

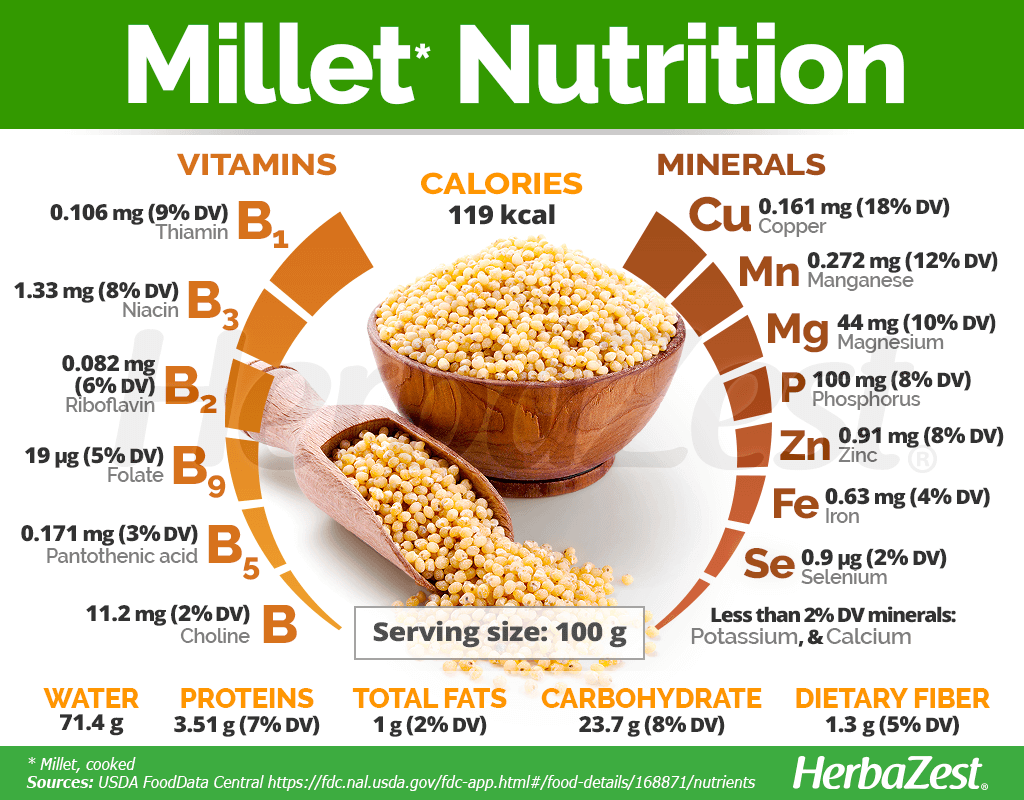

Millet Nutrition

Millet seeds are an excellent source of nourishment, providing most nutrients necessary for a balanced diet. In poor regions of the world, millet is a staple that brings sustenance and prevents nutritional deficiencies.

Millet's protein and carbohydrate content is similar to that of amaranth. It is also a good source of minerals like copper, essential for the production and transport of red blood cells; manganese, crucial for calcium absorption and adequate blood clotting; and magnesium, necessary for strong bones and proper metabolic functions.

Additionally, millet provides adequate amounts of phosphorus, which not only takes part in the formation of bones and teeth, but also works with B vitamins to maintain heart and kidney function, muscle response, and a healthy nervous system. Zinc, on the other hand, is essential for a strong immune system, supports metabolic function, and promotes wound healing.

Vitamin B1, or thiamin, helps strengthen the immune system and improves body's ability to withstand stressful conditions.

Moreover, millet provides adequate to good amounts of most B group vitamins, particularly B1 (thiamin), B3 (niacin), B2 (riboflavin), B6 (pyridoxine), and B9 (folate), all of them necessary to transform carbohydrates into glucose, which is the fuel used by the body to produce energy. They also help the body metabolize fats and protein as well as promote optimal brain function.

Millet's nutritional value is rounded off by the presence of smaller amounts of other vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid), choline, iron, and selenium.

100 GRAMS OF COOKED MILLET PROVIDE 119 CALORIES AS WELL AS 8, 7, AND 5% OF THE RECOMMENDED DAILY VALUE FOR CARBOHYDRATES, PROTEIN, AND DIETARY FIBER, RESPECTIVELY.

How to Consume Millet

Millet has been a traditional source of both nutrition and medicine, and its nutritional value is mostly reaped from natural forms.

Natural Forms

Dried. Millet seeds are sold dried, ready to cook in order to obtain their health benefits. Millet can replace rice and couscous, adding nutritional value to everyday meals.

Flour. Millet flour is commonly used in the countries where this cereal is widely cultivated. Being gluten-free, millet flour is also used to replace wheat in culinary preparations.

Flakes. Millet can also be consumed as morning cereal, providing essential nutrients and plenty of energy to go through the day. Millet flakes can also be added to salads, yogurt, and other recipes.

Herbal Remedies & Supplements

Essential oil. Millet essential oil can be taken orally to ease digestion and boost immunity. It is also popularly used externally as a hair moisturizer and revitalizer.

Tincture. Millet's health benefits can be obtained through this alcohol-based solution, which concentrates the antioxidant actions of the herb, aiding immunity and helping prevent chronic diseases.

Capsules. Millet capsules are made out of powdered millet seeds, which provide high amounts of soluble and insoluble fiber. As such, they are commonly consumed to regulate digestion and bowel movements as well as control blood sugar levels after heavy meals.

- Edible parts Seed

- Edible uses Protein

- Taste Mild

Growing

All millet varieties are considered hardy crops, extremely adaptable to any kind of soils, even those that are dry and poor in nutrients. Pearl millet is adapted for growth in dry conditions where there is low rainfall.

Growing guidelines

Most types of millet grow rapidly and do very well in acidic and infertile soils, with poor water-holding capacity. They have strong, deep rooting systems, which can make the most out of the little moisture available. However, better production can be obtained if millet is sown in well-drained, loamy soils.

Millets are propagated by seed, require warm temperatures for germination and development, and are sensitive to frost. Soil temperatures between 68 and 86°F (20-30°C) are ideal for successful germination. Millet seeds are normally planted in the latter half of May or early June, depending on the growing region.

Millet seeds must be planted with two inches (5 cm) of separation and topped with at least one inch (2.5 cm) of soil. Pearl millet is more commonly planted in rows 15-30 inches (38-76 cm) wide, spaced about one foot (30.5 cm). Compost can be added as the plants grow.

Although pearl millet grows fast and is generally able to outcompete weeds, it is important to maintain young seedlings in a weed-free seedbed since they may be susceptible to competition.

Pearl millet reaches maturity between 50 and 180 days after planting, depending on the variety. The crop is harvested by hand, either by cutting the spikes from the plant or by cutting the whole plant.

Millets are generally hardy crops; however, being adapted to extremely dry weather, they can be susceptible to fungal diseases, such as downy mildew, ergot, rust, and smut. They can also be attacked by a number of soil insects, such as aphids, armyworms, wireworms, and borers.

- Life cycle Annual

- Harvested parts Seeds, Leaves

- Light requirements Full sun

- Soil Medium (loam), Loamy sand, Well-drained

- Soil pH 6.6 – 7.3 (Neutral)

- Growing habitat Semi-arid regions

- Planting time Spring

- Plant spacing average 0.1 m (0.30 ft)

- Growing time 50 - 180 days

- Potential insect pests Aphids, Armyworms, Wire worms

- Potential diseases Fungi, Rust, Downy mildew, Smuts

Additional Information

Plant Biology

Pearl millet is a hardy, annual grass-crop which tillers widely and grows in tufts, with slender stems divided into distinct nodes. Millet leaves are linear or lanceolated, with small teeth and can grow up to 3.3 feet (1 m). The inflorescence takes the form of a spiky panicle, made up of many smaller spikelets where the grain is produced. Millet can reach 1.6-13.1 feet (0.5-4 m) in height depending on the cultivar and can be harvested after one growing season.

Classification

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) is a member of the Poaceae, a large family of tall grasses, which includes economically important crops like barley (Hordeum vulgare), maize (Zea mays), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), oats (Avena sativa), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), wheat (Triticum aestivum), and rice (Oryza sativa).

Varieties of millet

The Pennisetum genus comprises about 80-140 species, both annual and perennial. However, there are mainly five millet varieties of commercial importance: proso, foxtail, barnyard, browntop, and pearl. Proso millet is important for bird seed in the developed countries and for food in parts of Asia, whereas foxtail millet is staple in parts of Asia (mainly China) and Europe. Another variety, finger millet, is widely produced in the cooler, higher-altitude regions of Africa and Asia both as a food crop and as a preferred input for traditional beer. However, pearl millet is the most widespread and commercialized variety around the world.

Historical information

Millets are among the oldest of cultivated crops, and they have been a staple in semi-arid regions of South and East Asia, Africa and parts of Europe for millennia. According to historical records, some millet varieties, such as foxtail and proso millet, have been cultivated in China for over 10,000 years.

Pearl millet, one of the most popular millet varieties, was first cultivated over 4,000 - 5,000 years ago in the Sahel, an African region that extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, crossing the Sahara Desert and the Sudanian Savanna. From there, it spread to eastern and southern Africa, reaching the Indian subcontinent about 3,000 years ago.

In the United States, millet was not largely cultivated until 1875; it used to be grown only as a forage crop.

MILLET IS STILL A BASIC SOURCE OF NUTRITION FOR OVER 100 MILLION PEOPLE IN TROPICAL AREAS OF THE AFRICAN CONTINENT AND INDIA.

Economic Data

Millets are generally considered minor crops, except in parts of Asia (e.g., China and Russia) and Africa. The main producer of this cereal grain is India, followed by Nigeria and Niger. These countries account for about 94 percent of global output.

PEAR MILLET IS THE MOST IMPORTANT VARIETY IN REGIONS OF AFRICA AND ASIA, WHERE IT IS CRITICAL FOR FOOD SECURITY IN SOME OF THE WORLD'S HOTTEST, DRIEST CULTIVATED AREAS.

Other Uses

Food industry. Millets are used to produce many traditional food and beverage products.

Fodder. Millet is often used as a fodder for cattle in developing countries.

Farming. Millets are extensively used as a cover crop by farmers.

- Other uses Animal feed

Sources

- Cereals and Pulses, pp. 128-133

- Encyclopedia of Food and Health, pp. 748-757

- Penn State University, PlantVillage, Pearl Millet

- University of Georgia, Grain Millet

- University of Missouri, Growing Millets for Grain, Forage or Cover Crop Use

Footnotes:

PLoS One. (2014). Phytochemical and Antiproliferative Activity of Proso Millet. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4123978/

Oncotarget. (2017). Anti-inflammatory effects of millet bran derived-bound polyphenols in LPS-induced HT-29 cell via ROS/miR-149/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5650364/#R12