Rye, or cereal rye, is a tall grass whose origins have been traced back to Anatolia in Asia Minor, where it has been cultivated for over 6,000 years, since the dawn of agriculture. Nowadays, rye remains popular as a whole grain, offering great nutritional value and medicinal properties that have been widely studied by science. Keep reading to discover the health benefits of rye, its most popular uses, its rich history, and more

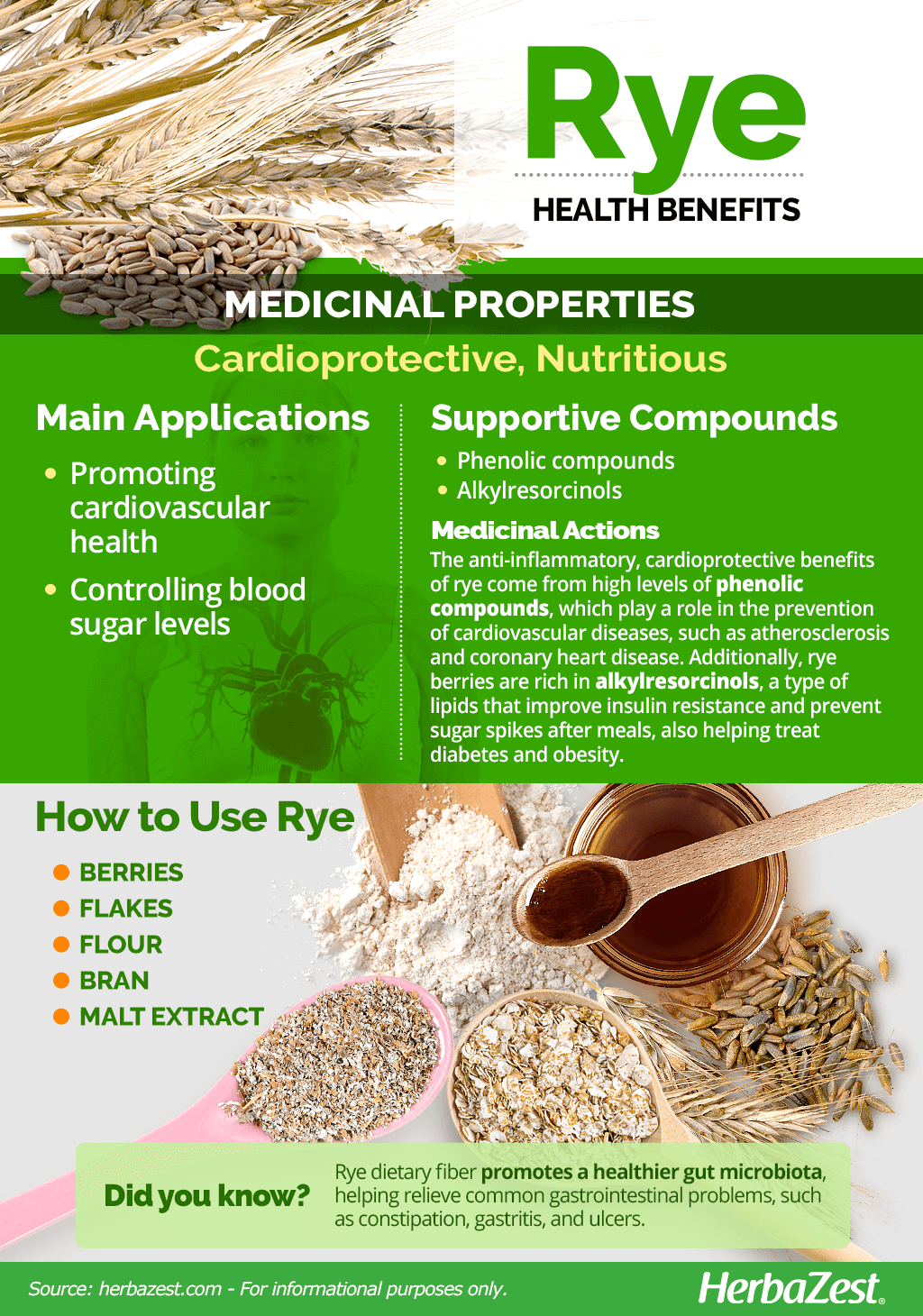

Rye Medicinal Properties

As a whole grain, rye is popularly consumed, mixed with other cereals such as buckwheat, millet, and wheat; however, rye has plenty of value on its own, with many culinary and industrial applications. Some of the most relevant health benefits of rye include:

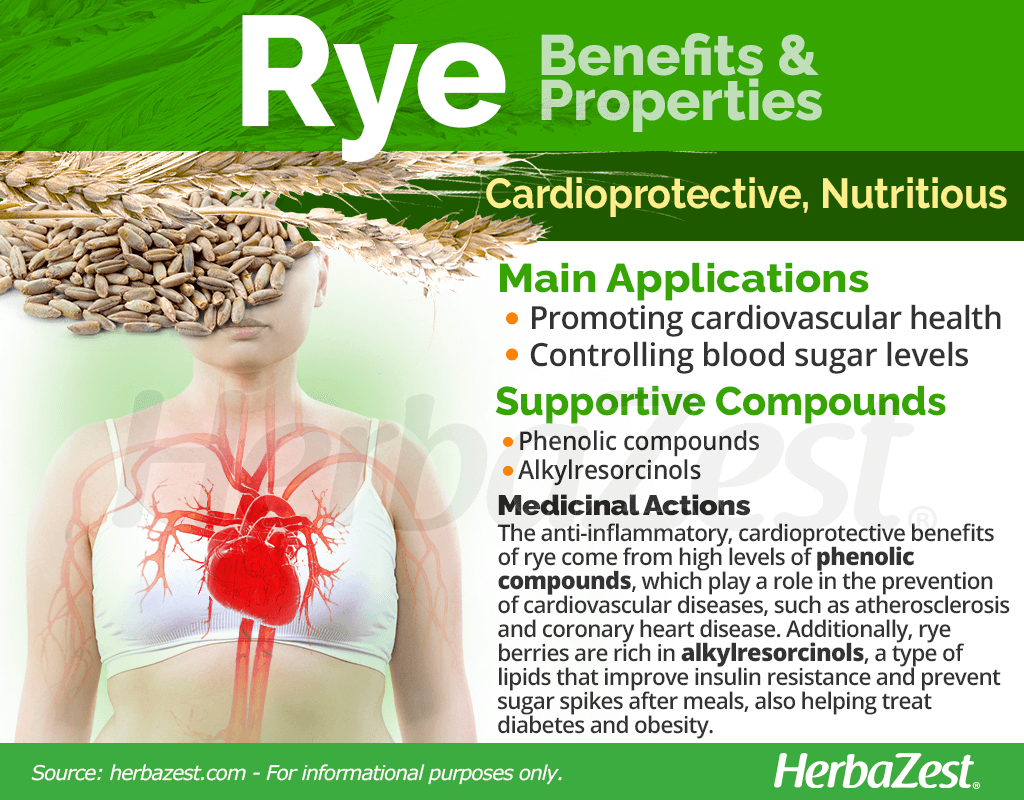

Promoting cardiovascular health. Rye grain is rich in antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds that not only help reduce harmful cholesterol levels but also the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Controlling blood sugar levels. Rye is rich in dietary fiber, which delays glucose absorption into the bloodstream, thus reducing spikes of sugar after meals.

Traditionally, rye has been used for:

Aiding digestion. Due to its fiber content, as well as other beneficial compounds, consuming rye has been associated to improvements in constipation, IBD, and other gastrointestinal problems.

- Relieving ulcers. Regular intake of rye can treat and prevent gastritis and ulcers caused by the presence of Helicobacter pylori.

Additionally, rye consumption has been shown to aid weight loss and help treat and prevent gallstones.

How It Works

The significant presence of phenolic compounds, mainly ferulic and coumarin acids, lends rye grain its anti-inflammatory properties, which have been shown to play a role in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease.1,2

Rye also provides alkylresorcinols, which are phenolic lipids that have been shown to improve insulin resistance and blood sugar levels after meals, helping to treat and prevent metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity.3,4

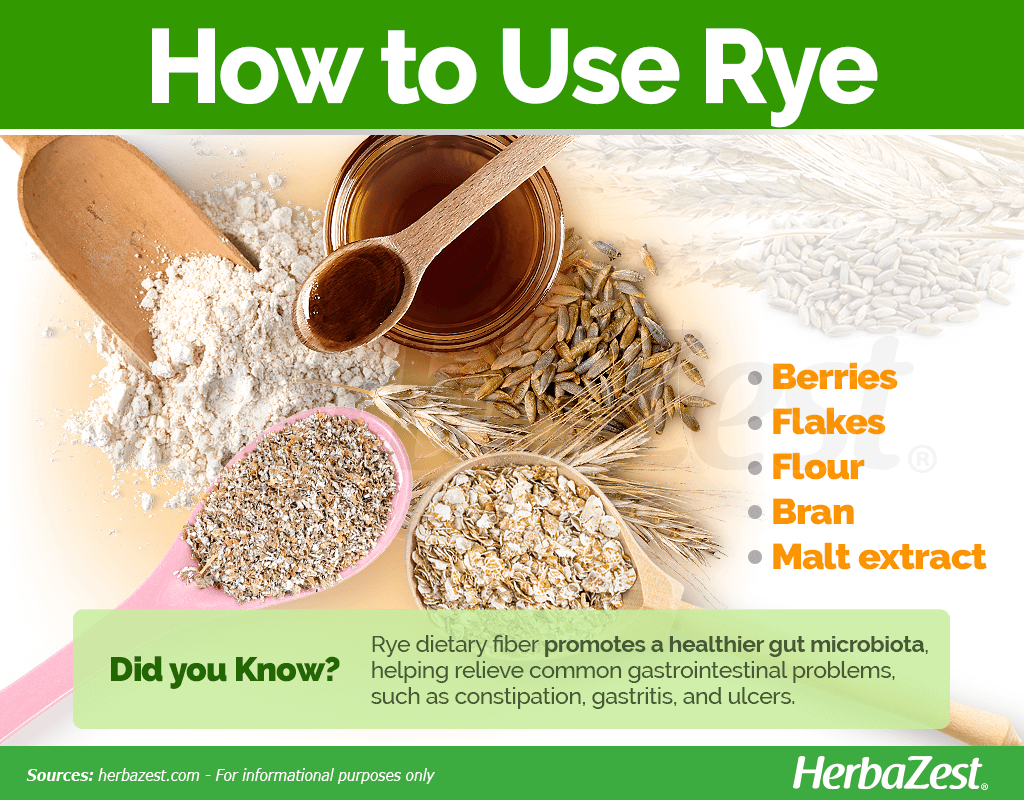

The particular fiber composition of rye promotes a healthier gut microbiota, which can relieve common gastrointestinal problems such as constipation, gastritis, and ulcers. 5,6

Other grains with that promote cardiovascular and metabolic health are amaranth, kaniwa, millet, quinoa, oats, and whole wheat.

Side Effects of Rye

The health benefits of rye are not for everyone, and the general public should consume rye containing products in moderation. Rye contains gluten, a plant protein that is also present in barley and wheat. This type of protein should be avoided by celiacs and gluten-intolerant individuals, since it can lead to serious damage of the small intestine, along with other undesirable symptoms, such as abdominal cramps and diarrhea. For other people, excessive rye consumption can lead to bloating and gas, which can be prevented by reducing the intake of this cereal or taking enzymes to facilitate its digestion.

- Medicinal action Cardioprotective, Nutritious

- Key constituents Phenolic compounds, alkylresorcinols

- Ways to use Liquid extracts, Food, Powder

- Medicinal rating (1) Very minor uses

- Safety ranking Safe

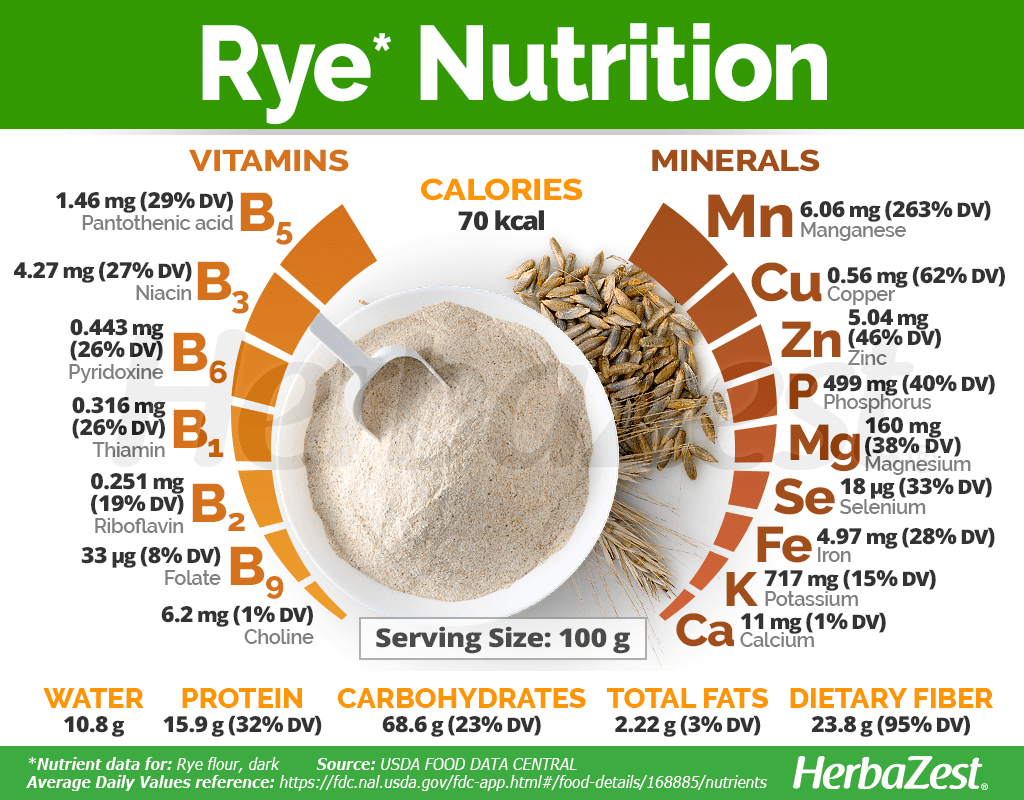

Rye Nutrition

Rye berries, or grains, are a powerhouse of essential nutrients, also providing a good deal of protein and dietary fiber. This is why rye flour is widely used in bakeries to add nutritional value to whole grain breads.7

A powerful combination of minerals makes rye a great addition to a balanced diet: manganese is necessary for the formation of bones and proper nervous function; copper and iron are both key for the production and transport of red blood cells and bone regeneration; phosphorus not only promotes optimal kidney function, helping to flush waste materials through urine, but also has a key role in the storage and use of energy; zinc is essential for human growth and development as well as for wound healing, skin health, and the immune system; magnesium plays a key role in proper muscle and nerve function, blood sugar levels, blood pressure, and protein metabolism as well as for DNA and bone regeneration; and selenium is instrumental for proper thyroid function, DNA production, and prevention of diseases caused by cellular oxidation.

Cereal rye is particularly rich in B vitamins, all of which are required for metabolic functions, transforming food into energy and ensuring proper cellular function. Additionally, rye berries are a good source of choline, essential for brain and nervous function as well as for cellular integrity, and folate, primarily involved in DNA repair and synthesis as well as helping prevent birth defects. Folate deficiency causes a variety of symptoms, such as canker sores, fatigue, weakness, and neurological problems.

100 grams of rye flour provide 325 calories, 32%DV of protein, 23%DV of carbohydrates, and 95%DV of dietary fiber.

How to Consume Rye

Being a very old crop, rye has been part of the human diet for millennia, long before wheat became a dietary staple. Rye has a strong reputation as a wholesome, soft grain, with a low gluten content (significantly less than wheat). The best way to obtain rye benefits is through culinary forms.

Rye berries can kept be in the pantry up to six months, but this shelf-life can be extended to a year in the fridge. Rye flour must be consumed within 3 months at room temperature, or 6 months if stored in the fridge.

Natural Forms

- Cooking tip

Rye berries not necessarily need overnight soaking; however, this process is useful to eliminate the excess of phytic acid, making rye nutrients more available and significantly shortening the cooking time.

Berries. Also known as rye grains, they undergo a cleaning process that removes the outer layer, or hull, which allows them to be consumed in different ways, mainly in soups and stews.

Flakes. Rolled in the same fashion as oats, rye flakes retain the same properties and nutritional content, with a shorter cooking time.

Flour. This is arguably the most popular rye product, since it can be used in a variety of baked goods, enriching their nutritional content.

Bran. Obtained from pulverizing the outer layers of rye berries, discarded during processing, rye bran is a rich source of nutrients and dietary fiber.

Malt extract. Obtained from fermented rye berries, and often combined with barley, malt extracts are commonly used to give better flavor and texture to bread and other baked goods. These extracts can be liquid or dried.

- Edible parts Seed

- Edible uses Beverage, Protein

- Taste Mild

Growing

Rye is considered the hardiest cereal, tolerant of cold climates and often used as a cover crop due to its ability to protect the soil from heavy rain and winds during the fall and winter seasons. Rye cultivation is not difficult; however, certain conditions are required for this cereal to thrive.

Growing Guidelines

Cereal rye grows better on well-drained, loamy soils, but it's tolerant of both heavy clay and poor, sandy soils.

Depending on a soil test, rye may need fertilizers for optimal growth, mainly phosphorus and nitrogen.

Rye seeds must be sown 3 inches (7 cm) apart, and about 0.8-10 inches (2.0-2.5 cm) deep in heavy soils, and 1.4-1.8 inches (3.5-4.5 cm) in sandy soils, with 15-30 inches (38-76 cm) space between rows.

Unlike other cereal crops, rye grows faster when sown in late fall, right before the first light frost. Its deep roots will protect the soil during the winter, which is particularly useful when rye used as a cover crop in fields where other cereals are grown.

The extensive root system of cereal rye makes it highly tolerant to drought; however, this crop needs a regular water supply to thrive. Nevertheless, care should be taken because excessive moisture during the fall can stunt growing.

Rye is less susceptible to pests and diseases than other cereal crops; however, it can be affected by armyworms and stinkbug, as well as by root-knot nematodes. Ergot is a fungus that can infect rye and other cereal crops, being toxic to both humans and livestock, but it can be prevented by treating the seeds before planting and after harvest.

- Life cycle Annual

- Harvested parts Seeds

- Light requirements Full sun

- Soil Medium (loam), Loamy sand, Well-drained

- Soil pH 5.6 – 6.0 (Moderately acidic), 6.1 – 6.5 (Slightly acidic), 6.6 – 7.3 (Neutral), 7.4 – 7.8 (Slightly alkaline)

- Growing habitat Cool temperate regions

- USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b, 5a, 5b, 6a, 7a, 7b, 8a, 8b

- Planting time Late summer, Fall

- Plant spacing average 0.15 m (0.49 ft)

- Growing time 120 - 150 days

- Potential insect pests Armyworms, Stink bugs

- Potential diseases Fungi

Additional Information

Rye taxonomy

Rye, also known as cereal rye and winter rye, is a fast-growing annual crop. Rye is considered the hardiest cereal since it tolerates cold weather and drought spells. Rye looks very much like wheat; however, it is taller, reaching up to 3-5 feet (0.91-1.5 m), and has flat blades that are greenish-blue, as well as an extensive fibrous root system that helps prevent nitrate leaching and groundwater contamination, as well as soil compaction, making it particularly useful as a cover crop and a good companion for other cereals.

Cereal rye cultivation is ideal for scavenging nitrogen, reducing soil erosion, adding biomass to the system, and suppressing weeds.

- ClassificationDid you know?

Though both are used for forage, rye grass (Lollium perenne) and cereal rye (Secale cereale) are different species with distinct applications.

Cereal rye (Secale cereale) belongs to the Poaceae, or grass family, which comprises over 10,000 species across 750 genera. It is known to contain "true grasses," many of them valuable crops like barley (Hordeum vulgare), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), maize (Zea mays), millet (Pennisetum glaucum), rice (Oryza sativa), oat (Avena sativa), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), and wheat (Triticum aestivum).

Varieties and Cultivars of Rye

The Secale genus is genetically diverse, and there are hundreds of species, annual and perennial, related to the common cereal rye, as well as a large number winter and spring varieties and cultivars adapted to a variety of conditions.

Historical Information

The English word rye is thought to have first been of Balto-Slavic origin, coming from the word ruzi, meaning whiskey.

The origins of rye have been traced back to Anatolia, over 6,000 years ago, where there are records of its domestication during the Neolithic, at the dawn of agriculture. Along with other cereals, wild rye (Secale anatolicum) naturally spread to Central Europe as a weed grass, later evolving into cereal rye (Secale cereale), which gained great popularity as a winter crop during the Middle Ages, due to its tolerance to poor soils and harsh weather.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the first European settlers brought rye to North and South America, and this cereal crop was preferred for making bread until the 19th century when wheat became more popular.

Economic Data

In spite of being a hardy crop, rye cultivation has experienced a decline in favor of wheat, a much more profitable cereal crop. However, rye is still used in the alimentary industry to enrich whole cereal breads and flour mixes. The main producers of rye are Germany, Poland, and Russia; however, the United States is an important producer, generating over $59.8 million only in 2020. Most of the rye in this American country is cultivated in Oklahoma, North Dakota, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Other uses

Fodder. Rye fields are popular for livestock grazing during the springtime.

Alcoholic beverages. Similar to barley, rye is often used as a base malt for beer and whiskey production.

Industrial fiber. Rye fiber, as well as other natural fibers from cereal crops, is being increasingly used in the production of strong, eco-friendly textiles.

Cover crop. Winter rye can be used as a cover crop to improve soil structure and prevent erosion.

Mulch. Some growers harvest winter rye to be used for mulching strawberries over winter or for mulching to suppress weeds between vegetable crop rows.

Weed management. The natural compounds that rye's aerial parts and roots produce can inhibit the germination of weeds that can compete with other crops.

- Other uses Alcohol, Animal feed, Textiles

Sources

- Agricultural Marketing Resource Center, Rye Profile, 2022

- Australian Government, Grains Research and Development Corporation, Cereal Rye

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Proposal for an International Year of Rye, 2018

- FoodData Central, Rye flour, dark

- Health Benefits of Rye

- International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Effects of Non-Starch Polysaccharides on Inflammatory Bowel Disease, 2017

- Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition, Ferulic Acid: Therapeutic Potential Through Its Antioxidant Property, 2007

- Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, An Overview of Alkylresorcinols Biological Properties and Effects, 2022

- Oregon State University, Cereal rye (Secale cereale L.)

- University of Arkansas, Cereal Rye as a Winter Crop

- University of Vermont, Cereal Rye Production Guide

- Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 1992

- Whole Grains Council, Storing Whole Grains | Health Benefits of Rye | Types of Rye

- Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Antioxidant effects of phenolic rye (Secale cereale L.) extracts, monomeric hydroxycinnamates, and ferulic acid dehydrodimers on human low-density lipoproteins, 2001

Footnotes:

- Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. (2001). Antioxidant effects of phenolic rye (Secale cereale L.) extracts, monomeric hydroxycinnamates, and ferulic acid dehydrodimers on human low-density lipoproteins. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11513715/

- Nutrition Journal. (2017). Effects of whole grain rye, with and without resistant starch type 2 supplementation, on glucose tolerance, gut hormones, inflammation and appetite regulation in an 11-14.5 hour perspective; a randomized controlled study in healthy subjects. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5401465/

- American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. (2016). Plasma alkylresorcinols, biomarkers of whole-grain wheat and rye intake, and risk of type 2 diabetes in Scandinavian men and women. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27281306/

- Frontiers in Nutrition. (2022). The Effect of Rye-Based Foods on Postprandial Plasma Insulin Concentration: The Rye Factor. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9218669/

- European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. (2006). A combination of fibre-rich rye bread and yoghurt containing Lactobacillus GG improves bowel function in women with self-reported constipation. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16251881/

- Nutrients. (2022). The Effects of High Fiber Rye, Compared to Refined Wheat, on Gut Microbiota Composition, Plasma Short Chain Fatty Acids, and Implications for Weight Loss and Metabolic Risk Factors (the RyeWeight Study). Retrieved April 1, 2024, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9032876/

- Food Science and Nutrition. (2021). Structural and nutritional portrayal of rye‐supplemented bread using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8565228/