Hailing from southeast Asia, taro is an herbaceous plant, also known as arvi (Indian subcontinent), caladium, dasheen (Thailand and other Asian countries), and elephant ears, among other popular names. Valued by gardeners as a beautiful ornamental, it has been cultivated for centuries in tropical and temperate regions of Africa, Mediterranean, Asia, and Oceania for nutritional and medicinal purposes.

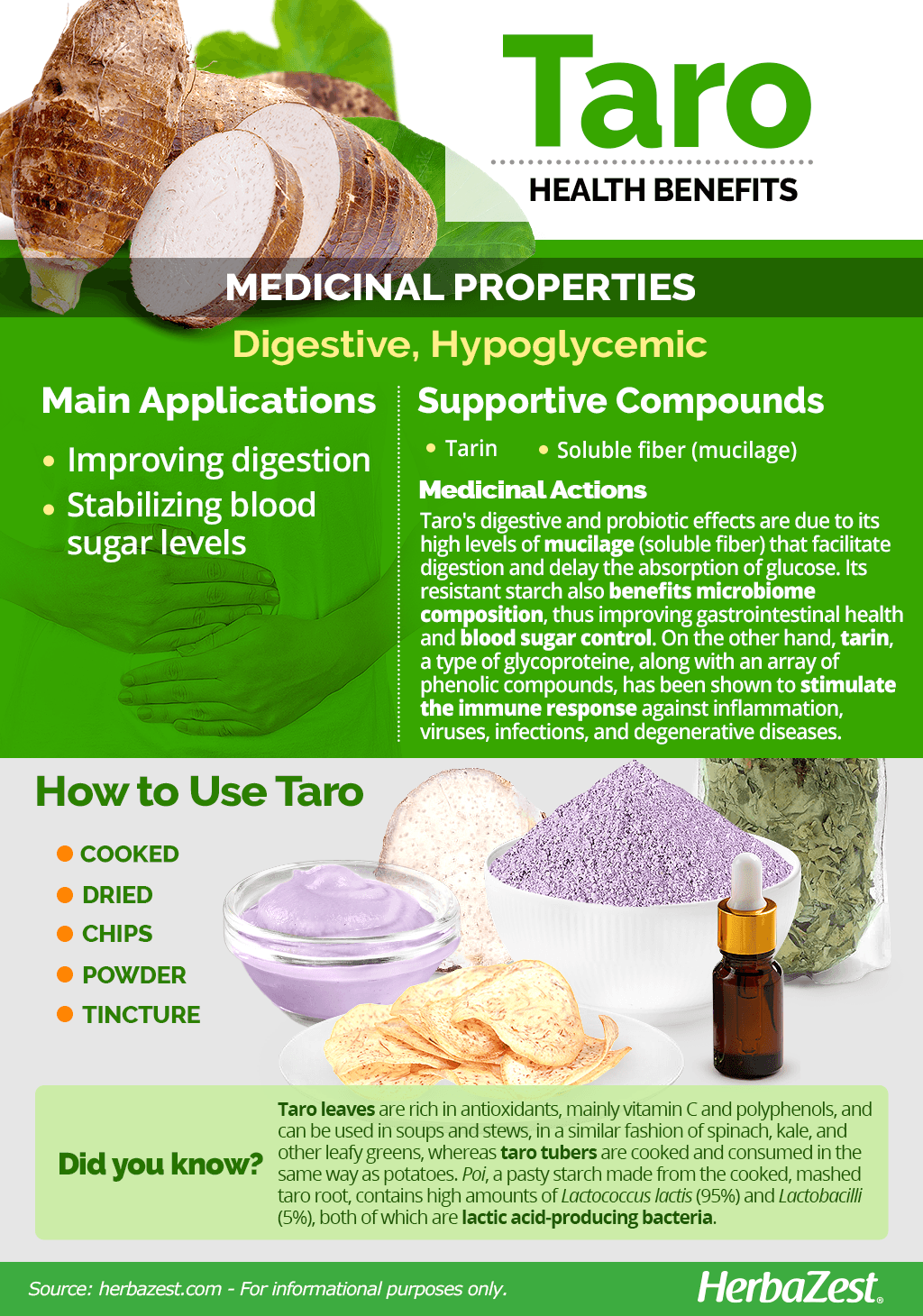

Taro Medicinal Properties

Benefits of Taro

Improving digestion. Due to its impressive fiber content, taro root not only promotes smooth digestion and healthy bowel movements, but its resistant starch is also thought to benefit gut flora, which is ideal for people with gastrointestinal disorders, such as Chron disease and irritable bowel syndrome as well as for those with Candida infections.

Stabilizing blood sugar levels. Taro root fiber has been shown to delay glucose absorption, preventing sugar spikes after meals, which makes it a great functional food for people with hyperglycemia and diabetes.

Additionally, the immune boosting properties of taro have been suggested by different studies as well as its ability for reducing inflammation. The taro plant is also rich in antioxidants, which can prevent degenerative and age-related diseases. Taro has been traditionally used as a popular remedy for a variety of health conditions, such as asthma, skin problems, neurological disorders, internal hemorrhaging, pneumonia, and hypertension.

SCIENCE IS ACTIVELY EXPLORING THE POTENTIAL OF TARO AS A NUTRACEUTICAL FOOD FOR DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT.

How It Works

Taro's digestive and probiotic effects are due to its high levels of mucilage (soluble fiber) and carbohydrates (resistant starches), which not only facilitate digestion and delay the absorption of glucose but are also thought to benefit microbiome composition, thus contributing to improve gastrointestinal health as well as aiding with weight management and blood sugar control.1,2 Poi, a pasty starch made from the cooked, mashed taro root, contains high amounts of beneficial bacteria, mainly Lactococcus lactis (95%) and Lactobacilli (5%), both of which are lactic acid-producing bacteria.3

On the other hand, tarin, a type of glycoprotein, along other biochemical compounds, such as polysaccharides, flavonoids, alkaloids, sterols, tannins, and phytates, has been shown to stimulate the immune response against inflammation, viruses, infections, and degenerative diseases. Studies suggest that dietary interventions including taro root may be useful as a complementary strategy for improving overall health and manage immune-related conditions. 4,5

TARO ROOT CAN BE IDEAL TO ENRICH THE DIET OF PEOPLE WITH DIABETES AND GLUTEN-INTOLERANCE AS WELL AS FOR THOSE WITH GASTROINTESTINAL CONDITIONS, LIKE DIARRHEA, GASTROENTERITIS, IBS, AND FOOD ALLERGIES.

Other herbs with digestive properties are arrowroot, arracacha, potatoes, and sweet potatoes, whereas yacon and stevia also help with blood sugar control, and immune boosting properties can be found in astragalus, echinacea, and soursop.

Side Effects of Taro

Taro root is considered generally safe for consumption in moderate amounts; however, taro leaves and tuberous roots are rich in non-absorbable salts called oxalates, which can increase the risk of kidney stones over time.

Cautions

Direct contact with fresh taro leaves can cause skin irritation and they are edible only after been cooked. People who suffer from kidney stones or gallstones should consume this tuberous vegetable in moderation.

- Medicinal action Digestive, Hypoglycemic

- Key constituents Tarin, soluble fiber

- Ways to use Hot infusions/tisanes, Food, Tincture, Powder

- Medicinal rating (2) Minorly useful plant

- Safety ranking Safe

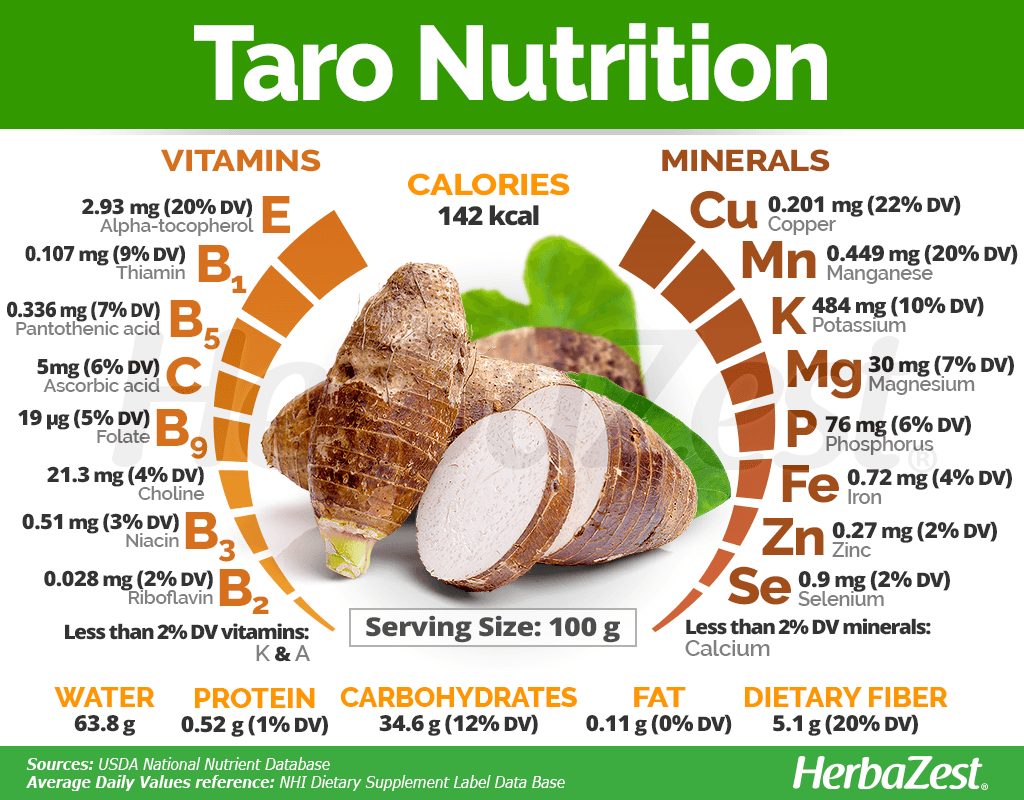

Taro Nutrition

Mostly composed by resistant carbohydrates, it can come as a surprise the fact that taro has a lot to offer in the nutrition department. This tuber provides a wide range of vitamins and minerals that are essential in the human diet.

Beyond their impressive content of soluble fiber, with probiotic effects, taro roots are a great source of copper and manganese, both essential minerals for many bodily functions. Copper plays a key role in energy production by protecting the integrity of the cells, which not only make possible the production of hemoglobine, but also the synthesis of connective tissue and neurotransmitters. On the other hand, manganese is necessary for the metabolic procesess of amino acids, cholesterol, glucose, and carbohydrates as well as for bone formation, reproductive function, and immune response. Potassium is also present in good amounts in taro root, and it is essential for nerves function and muscle contraction. Being an electrolite, potassium also keeps in check the levels of sodium in the bloodstream, naturally lowering blood pressure.

When it comes to vitamins, taro root doesn't fall short either. It is rich in vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol), a fat-soluble nutrient with antioxidant properties, which protects the cells from free-radicals damage that comes from processed foods, air pollution, and sunlight exposure (UV light), thus preventing the onset of degenerative and age-related diseases. Taro also provides adequate amounts of other essential vitamins, such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid) and B-group vitamins, mainly B1 (thiamin), B5 (pantothenic acid), and B6 (folate).

100 GRAMS OF COOKED TARO ROOT PROVIDES 142 CALORIES, 12%DV OF CARBOHYDRATES, AND 20%DV OF DIETARY FIBER.

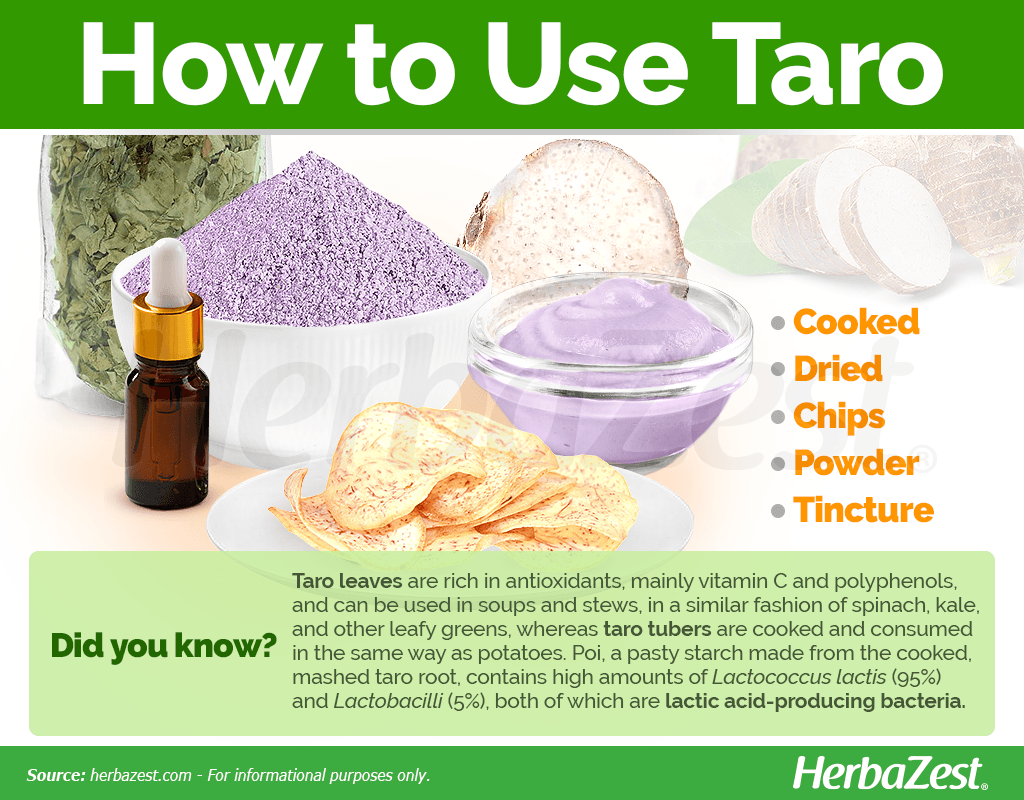

How to Consume Taro

Taro leaves and corms, or tuberous bulbs, are mainly used in culinary preparations. They are cooked and used in various dishes, such as soups, stews, curries, and desserts. Taro tubers have a mild, nutty flavor and a texture similar to potatoes.

Natural Forms

Cooked. Taro leaves and roots must be cooked to reduce their oxalate content before consumption. While taro tender leaves are rich in antioxidants, mainly vitamin C and polyphenols, and can be used in soups and stews, in a similar fashion of spinach, kale, and other leafy greens, taro tuberous roots are cooked and consumed in the same way as potato.

Dried. Sun-dried taro leaves retain their antioxidant power, and they can be added to culinary preparations or infusions in order to reap their medicinal benefits.

Chips. Alone and mixed with other veggies, taro chips, with a crunchy texture and a slightly nutty flavor, are a very popular snack, and probably the most well-known form of taro roots outside of its native areas. However, since snacks are usually high in sodium, reading the labels before consuming taro chips is a good idea.

- Did you know?

Taro powder is a key ingredient in popular Asian beverages, like taro milk tea, taro boba tea, or taro latte, all delicious ways to take advantage of the digestive and probiotic properties of taro.

Powder. Taro roots are dehydrated and pulverized to obtain a fine powder, or flour, that can be used as a thickening agent in sauces and soups, added to smoothies, or replace wheat flour in gluten-free preparations.

The binding properties of taro have been shown to be stronger than the ones in cornstarch and other glutinous herbs6, and its mucilage content makes it ideal to replace xantham gum in gluten-free recipes, just adding a quarter of it instead regular wheat flour.

Herbal Remedies & Supplements

Tincture. The antioxidant properties of taro leaves can be obtained by maceration in a neutral alcohol. This concentrated form has been shown to have antihypertensive and diuretic effects.7

Due to its content of beneficial bacteria, taro powder is often combined with other ingredients in probiotic supplements for immune support and vaginal health.

- Edible parts Leaves, Root

- Taste Mild

Growing

Native to Southeast Asia, taro, also known as elephant ears and malanga, has been cultivated for centuries as a food crop in many tropical parts of the world, and its starchy tuberous roots are an important source of nutrition in many cultures. Due to its attractive foliage, taro is also grown as an ornamental plant (as an elephant ear variety) in gardens and landscapes, given the right climate and soil conditions.

Growing Guidelines

- The taro plant thrives in warm, humid climates and requires ample moisture and sunlight to grow well.

There are two forms of propagation for taro: corm or tuber division or planting the suckers that emerge from the base of the plant.

Taro can be planted in wetlands and dry soil; however, the wetland varieties of taro are more productive (50-100 tons per hectare), whereas wetland crops produce around 25-50 tons per hectare.

While flooding conditions allows taro to grow relatively free of weed plants, and watering is not a concern, when cultivated in dryland, taro plants not only need adequate irrigation, but the soil have to be periodically cleared from weeds.

- While fertilizer applications are ususally unnecessary with wetland taro, when cultivated in dryland, taro plants may experience potassium deficiency, and periodic soil tests are recommended.

Taro plants are often attacked by fungal diseases, such as Phytophthora blight (Phytophthora colocasiae), Pythium root and corm rot (Pythium spp.)as well as leaf spot, dry rot and root rot, particularly when this crop is cultivated in wetlands.

- Many pests feed on the taro plant, including armyworms, ants, aphids, beetles, planthoppers, snails, and spider mites.

- Life cycle Perennial

- Harvested parts Leaves, Bulb

- Light requirements Full sun

Additional Information

Taxonomy of Taro

The taro plant is a perennial species that grows from an underground bulb, or corm, which is a swollen stem structure that stores nutrients. The plant has large, heart-shaped leaves that resemble the ears of an elephant, which gives it the common name "elephant ear plant." The leaves can vary in color, ranging from green to purplish-black.

Classification

The taro plant (Colocasia esculenta) is part of the Colocasia genus, a group of flowering plants belonging to the Araceae family, which is composed by terrestrial or aquatic shrubs, vines, or herbs, with 4,000 species distributed across over 140 genera. It is commonly known as taro or elephant ear plant.

Taro is often confused with another tuberous root popularly called tannia (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), with a very similar aspect, which also produces an edible, tuberous root but belongs to a completely different genus.

Varieties and Cultivars of Taro

The genus Colocasia, including Colocasia esculenta, encompasses over 20 species distributed across tropical and subtropical areas of Asia. These plants, colectively called elephant's ear, are valued for their edible roots and striking foliage, making them significant as a food crop, but also as ornamentals.

There are currently over 200 cultivars of taro, including edible and ornamental plants from both wetland and upland types.

Historical Information

The origins of taro can be traced back to the tropical and subtropical regions of southeast Asia. This herbaceous plant was introduced into Japan more than 2500 years ago, and early Polynesians spread it across the Pacific islands and Oceania, where it became a staple food, particularly in Hawaii, New Zealand, and Indonesia, where it is popularly known as dasheen.

In 1769, Captain Cook saw a plantation of Colocasia esculenta in New Zealand and adopted the name taro from the local maori language.

Popular Beliefs

Taro have had great cultural significance for the Hawaiians, who have associated it with their ancestors and gods. According to a hawaiian legend, the first taro plant grew from the dead body of Haloa-naka, the stillborn son of Wakea (father of the sky) and Ho'ohokulani (daughter of earth), and was called Haloa, which roughly translates to "everlasting breath". The traditional ceremony of life includes the consumption of poi (a paste made from the cooked, mashed taro root), as a symbol of the unbreakable link between the hawaiians and their ancestors.

Economic data

Though taro is still an underrated vegetable in many parts of the world, but it is considered a staple in the diet of more than 500 million people across Asia, Africa, Central America, and the Pacific Islands.

Nigeria is the largest producer of taro root, with a 32.4% of the global market, followed by China, Cameroon, Ghana, and Papua New Guinea. In 2014, the global production of taro root reached 10.1 million tons.

In South Mediterranean countries, taro root is even more popular than potatoes.

Other uses

Pharmaceutical industry. Taro powder is often used as an excipient in all kind of pills as well as for the production of gelatin capsules.

Fodder. Taro is commonly used to feed cattle in farms.

Gardening. Elephant's ear plants, includin taro, are very popular as ornamentals in gardens and landscapes.

Sources

- Agro productividad, Evolution of the Agri-Food Chain Concept in the 21st Century: The Taro Case, 2020

- Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health, Fruits and Vegetables, 2010

- Biopreservation and Biobanking, Conserving and Sharing Taro Genetic Resources for the Benefit of Global Taro Cultivation: A Core Contribution of the Centre for Pacific Crops and Trees, 2018

- Center for Livestock Research for Rural Development, Survey of taro varieties and their use in selected areas of Cambodia

- Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology, Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott as an Alternative Energy Source in Animal Nutrition, 2014

- Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary origins of taro (Colocasia esculenta) in Southeast Asia, 2020 Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops, 1993

- Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second Edition)

- Food Science and Technology, Formulation and characterization of functional foods based on fruit and vegetable residue flour, 2015

- Genetic Improvement of Vegetable Crops

Footnotes:

- International Journal of Food Science + Technology. (2023). Physicochemical and digestive properties of Lipu taro (Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott) flour and starch. Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://ifst.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ijfs.16307

- Polymers (Basel). (2022). A Concise Review on Taro Mucilage: Extraction Techniques, Chemical Composition, Characterization, Applications, and Health Attributes. Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8949670/

- Nutrition in Clinical Care. (2004). The Medicinal Uses of Poi. Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1482315/

- International Journal of Molecular Sciences. (2021). Anticancer and Immunomodulatory Benefits of Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Corms, an Underexploited Tuber Crop. Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7795958/

- Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. (2018). Tarin, a Potential Immunomodulator and COX-Inhibitor Lectin Found in Taro (Colocasia esculenta). Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://ift.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1541-4337.12358

- Jornal of Food Science and Technology. (2013). Studies on physicochemical and pasting properties of Taro (Colocasia esculenta L.) flour in comparison with a cereal, tuber and legume flour. Retrieved July 13, 2023, from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24425892/

- Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. (2012). Antihypertensive and Diuretic Effects of the Aqueous Extract of Colocasia esculenta Linn. Leaves in Experimental Paradigms. Retrieved July 3, 2023, from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3832168/